Initially not considered in the same class as Williams, Boggs, and Mattingly, he proved himself a unique player with a personality to match.

Hall of Fame outfielder Tony Gwynn died on Monday. There is justice in the fact that his passing will be mourned with a greater intensity than he was sometimes celebrated during his career. In early 1986, Peter Gammons, then of Sports Illustrated, convened Wade Boggs, Don Mattingly, and Ted Williams for a roundtable on hitting. Williams, of course, was the self-proclaimed greatest hitter who had ever lived and had the .406 batting average to prove it as well as a plaque on the wall at Cooperstown. Boggs, 28 that season, had to that point won two of an eventual five batting titles. Mattingly, 25, had already won his sole batting title in 1985, though he'd come close on a couple of other occasions.

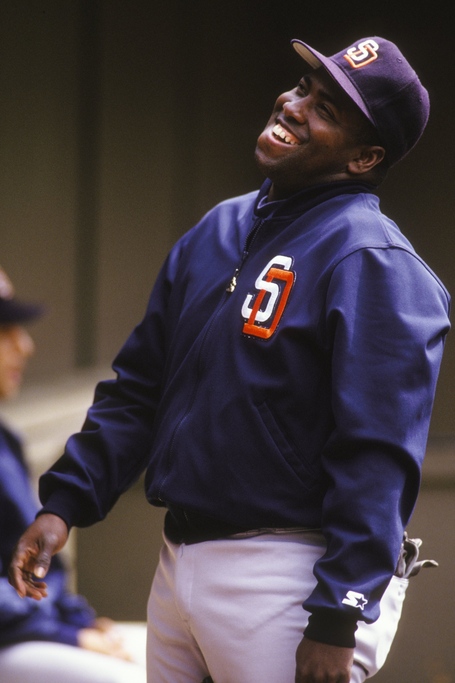

Tony Gwynn, then going on 26 and the owner of the .351 batting title that had helped drive the 1984 San Diego Padres to a surprise World Series appearance was, insofar as we know, not invited. Seven more batting titles, a total of 3,141 hits, and a career .338 average lay in his future, all achieved in 20 glorious seasons with the Pads. After hitting .289 in his 54-game 1982 debut, he never hit less than .309 in any year and peaked during the strike-shortened 1994 season with a .394 batting average. As with Boggs, he would join Williams in having his likeness placed in the Hall of Fame shrine.

Later, he would become friends with Williams, and, as so many younger players did, relish talking hitting with him. But that recognition from the San Diego native hadn't yet come. SI let that roundtable breathe, allowing Williams, Boggs, and Mattingly roll on for page after page. At one point, Gammons asks Williams to name some favorite active major-league hitters. Teddy Ballgame's answer:

I love Dale Murphy. He's really got style. I like Mike Marshall's style. I like Bobby Horner, but Horner hits the pitcher's pitch too much. I like Keith Moreland's style. Greg Brock's got style, and he's got great mechanics; I don't understand why he doesn't do better. Darryl Strawberry's big, strong and really quick. He could eventually get a little more opened up and hit 45 home runs. I love to watch him. When you see him on the ball field, you just can't keep your eyes off him. Guys like that don't come along often.

![]() More from our team sites

More from our team sites ![]()

![]() More from our team sites

More from our team sites ![]()

Yes, Greg Brock, a career .248/.338/.399-hitting first baseman came to the great man's mind more easily than did Gwynn. Perhaps that was because Brock was built in the basic left-handed power-hitters mold, whereas Gwynn wasn't like anybody else. There's no model of player that's similar. He was a high-contact hitter, 10 times the hardest man in the National League to strike out. After he gained weight later in his career, the 5'11" outfielder might have reminded you a bit of another batting-title winner, Kirby Puckett, 5'8", the Minnesota Twins outfielder who was about seven weeks older than Gwynn and also died sadly young -- both finished up their careers looking a bit like human bowling pins.

But remembering Gwynn that way does him a disservice. When he first game up he was thin and speedy, stealing up to 56 bases in a season and was a deserving five-time Gold-Glove winner in right field. Oddly, as Gwynn's conditioning slipped and he was more frequently injured, his batting averages continued to rise. He hit .332 in his 20s, .344 in his 30s, and slipped all the way to .323 in two attenuated seasons in his 40s. Foot and knee problems robbed him of speed and range -- he remained good at picking his spots -- from 1993 to 2001 he stole 70 bases against only 19 times caught -- he maintained the ability to put the bat on the ball. He faced Greg Maddux 107 times, hit .415, and never struck out. He hit .303 against fellow lefty Tom Glavine and struck out twice in 105 times at the plate. Split-finger master Mike Scott got him all of three times in 95 PAs. He hit .321 against Orel Hershiser, .444 against John Smoltz.

The sometime-closer Jeff Brantley struck him out once in 33 plate appearances. The rest of the time, Gwynn merely went 16-for-28 against him for a .571 average. The pitcher who got him to swing and miss the most? Nolan Ryan, with nine Ks. Gwynn hit .302 against him. Second-most? Ron Darling with six. Gwynn hit .441. Three other pitchers got him six times each -- the tough lefty John Tudor, against him Gwynn hit .348, and two disparate hurlers who actually did give him problems -- the righty Dwight Gooden and the lefty John Smiley, who somehow held him to .205 in 41 PAs. He couldn't do much with another southpaw, Denny Neagle, either. For the most part, though, familiarity bred contempt: Gwynn faced 97 pitchers 30 or more times in his career. He hit over .300 against roughly three-quarters of them.

"Contempt" is another word that isn't fair to Gwynn; his public persona was very much that of the Ernie Banks of his day, a cheerful, professional man who loved to play baseball, was dedicated to refining his art by any possible means, including the then-innovative study of videotape. The Padres were a mess of clubhouse resentments in the 1980s, driven by radical conservative John Birch Society members, drug abusers, and those who simply resented playing for the moralistic owner of McDonald's Joan Kroc, and her team president Ballard Smith, not coincidentally her son-in-law. Some Padres, such as the pitcher Eric Show (also now deceased), fell into at least two of the three camps. Gwynn seemed to float above it all, just showing up to hit his line drives.

It was no surprise at all that he went into coaching at San Diego State University. Unlike Boggs, Williams, Rogers Hornsby, or Ty Cobb, there didn't seem to be anger driving all those .300 averages, just a respect for excellence. Williams, Cobb, and Hornsby mostly couldn't teach when they tried to coach or manage, were in fact horrifically bad at it; when your driving force is a compulsive rage to excel, it's difficult to relate to others whose motive might be just to have fun playing baseball and do well at it along the way. Whatever animated Gwynn was far more -- and please forgive the use of this term on the day that cancer laid him low -- benign. It is hard to picture Gwynn without a smile on his face.

So, you had consistency, personality, professionalism, and hitting and baserunning results that seemed out of an earlier age. Gwynn was better than those pre-1920 guys, though, with more pop and baserunning ability that was legitimate rather than an imperative forced on every player at a time when extra-base hits were hard to come by. When New York Giants outfielder George Burns stole 40 bases in 1913, he was caught 35 times. When Gwynn stole 40 bases in 1989, he was caught 16 times. That's the difference between a style of play in which the baserunner went because there was no other way off of first and going because you could go, because you had the ability.

Probably the closest thing we have to Gwynn today is Ichiro Suzuki. Gwynn was better than Ichiro as well, though this is unfair to the latter since he spent some prime years playing in Japan. Both players had more than their share of infield hits, but playing mostly in an era which was much less kind to hitters than Ichiro's Seattle 2000s, Gwynn manifested more power. Push Gwynn's career forward about 10 years, put him in the right ballpark, and Williams might have lived to see a new member of the .400 club.

Most likely, though, all comparisons are useless. There hasn't been anyone like him and there may not be again. Throughout his career, Gwynn's amazing eye-hand coordination was frequently remarked upon. Nature manufactures enough ballplayers that each June teams draft about 1200 of them, and that doesn't count the international signings or the domestic guys that get scooped up even though they weren't deemed worthy of a draft pick, but it doesn't give out what Gwynn had very often. Boggs and Mattingly had the same thing to some degree, but they were relatively slow corner infielders. Boggs got the eye to draw 100 walks a season; Mattingly got the power via doing unnatural things to his spine; Gwynn got the preternatural contact ability of both, plus the speed, the arm, and the charm.

It's possible that there's another Gwynn out there somewhere, or will be one day. It's also possible that during the slugging, steroidal years we only just exited, scouts weren't even looking for it. Mark McGwire types were far more in demand than speedy line-drive hitters. We will never know.

This past weekend, Jimmy Rollins was celebrated for becoming the Phillies' all-time leader in hits. Rollins has been a very fine player in his career and could conceivably be a Hall of Famer himself one day. Yet, when one thinks of who the Padres' career leader in hits is, we see how empty such designations can be. Sometimes they indicate longevity and durability more than excellence. In Gwynn's case, though he was not without a few faults related to conditioning as he aged, it was most definitely the latter. Unique is an overused term, but it applies here.

I regret Tony Gwynn's early passing, the loss to his family, friends, teammates, and many fans, but almost as much as that, I regret the passage of time and the extinction of someone who gave and continued to give the game so much. I want it to be 1984 again for a little while, with Gwynn, 24 years old, emerging as a star, slashing doubles and triples from the second spot in the Padres' batting order. In fairer universe, we'd get to see him that way again, even if just for one more time.